Once again, the winds of change are wafting through The Palm Beaches.

Sure, the upscale, celebrity crowd is still slipping into très chic Palm Beach – to relax, to see and to be seen – just as it did a century ago. And yes, this little island of about 8,800 people remains the classic getaway for 21st- century jetsetters. It is, after all, the social, political and financial headquarters of the very rich.

None of that‘s actually changed at all. Just ask Manny Bornia, managing director of Collab Hospitality and restaurateur at Hai House. “Palm Beach is a playground for old and new wealth, and it’s pretty incredible who’s in town at any given time,” he says. “In our restaurant, we see everyone from the Kennedy family to Maury Povich and Connie Chung.”

But the season – the one railroad magnate Henry Flagler helped establish in the late 1800s, when denizens of the northeast descended on Palm Beach from Presidents Day until Easter – is shifting. “You still have many families that go back to the northeast,” he says. “But more are staying and living on the northern side of the island.”

Across Lake Worth Lagoon, in West Palm Beach, cranes dominate the downtown skyline, as this city of 110,000 goes vertical. Once home to those who worked in Palm Beach, West Palm has come into its own. All of a sudden, day-tripping tourists from Miami and Fort Lauderdale are exploring it, thanks to express train service via Brightline, soon to become Virgin Trains USA.

“We’re seeing a softening of the season because those people have access to the city and they didn’t have that before,” he says. “It’s come full circle with the railroad – the new Brightline is riding on the rails that Flagler put together.”

The tourists are coming to see and experience all The Palm Beaches have to offer. This is a place where pedigrees matter – and that’s especially true for the area’s ever-evolving architecture. And four stellar examples tell that story well:

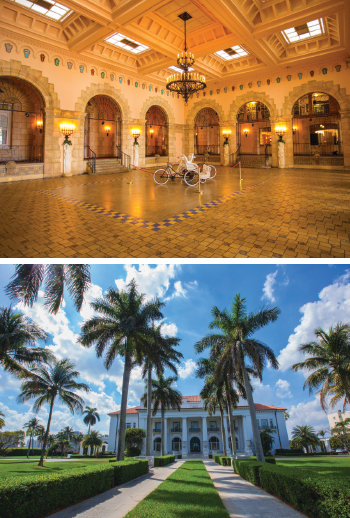

The Flagler Museum

In 1902, Flagler commissioned New York-based Carrère and Hastings to design his 75-room, white-columned Palm Beach mansion. He called it Whitehall, and gave it to his wife as a wedding gift. More than a residence, it was a neoclassical, Beaux Arts articulation of the Gilded Age – a palace for the classes, not the masses.

Whitehall – now open to the public as the Flagler Museum – laid down a marker of quality for all that followed. “It’s the most important historic structure of major significance, and the oldest in Palm Beach,” says local historian Rick Rose. “It’s definitely Number One – and one of two National Historic Register properties here.”

Carrère and Hastings would design the New York City Public Library and later, landmarks in Rome, Paris, London and Havana. Flagler would extend his railroad all the way to Key West. And Palm Beach would be transformed into a lush and lavish boomtown.

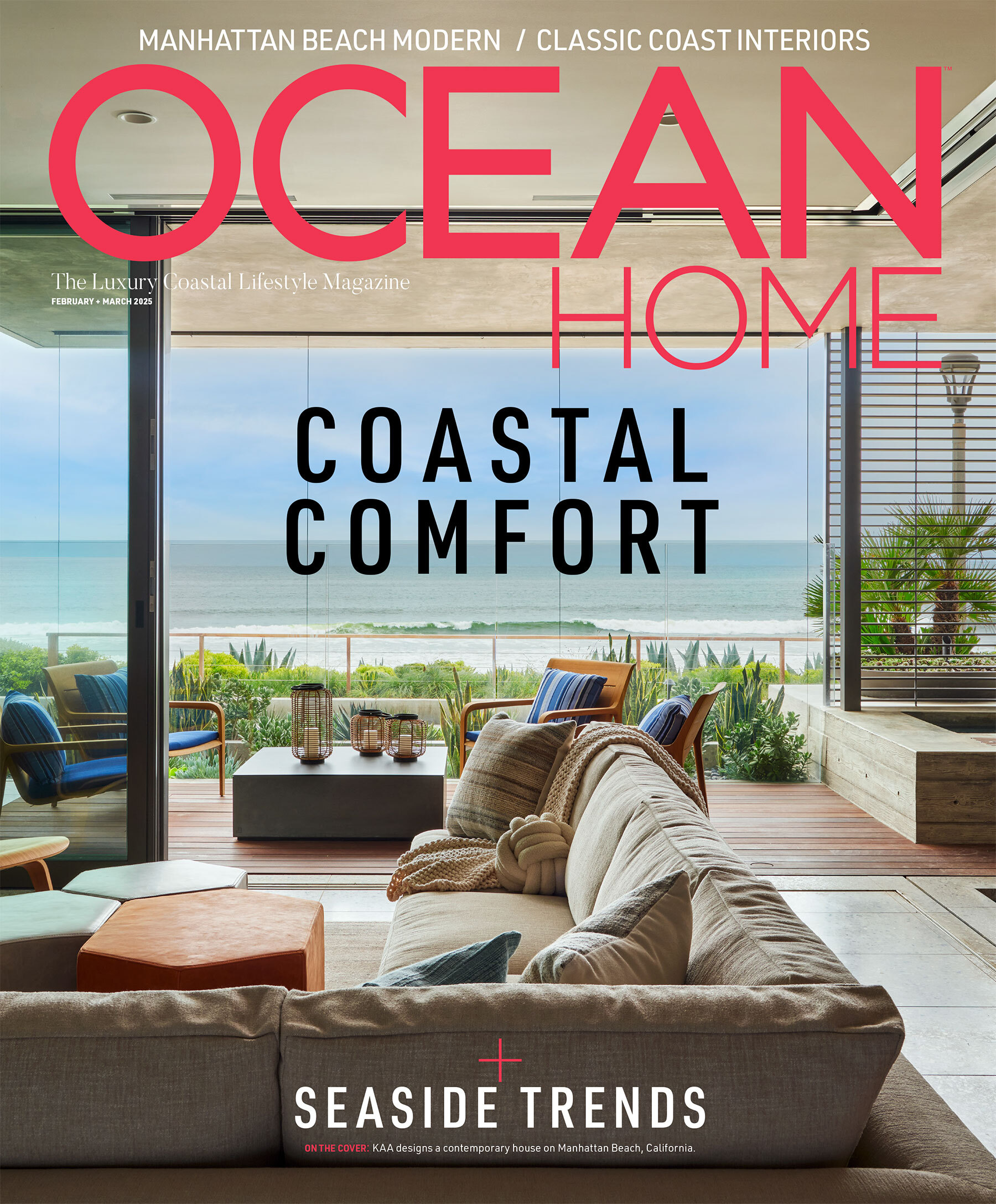

The Breakers

In 1896, Flagler built The Palm Beach Inn, then doubled its size in 1901and renamed it The Breakers. It burned in 1903, was rebuilt and opened again in1904.

Alas, by 1925 The Breakers was in flames again. Flagler had died in 1913, so his descendants looked to New York for a more permanent structure, hiring Schultze & Weaver. That firm would go on to design jewels like the Pierre, The Sherry-Netherland and the Waldorf Astoria, each still standing in Manhattan today.

Their seven-story design for The Breakers, modeled on the Villa Medici in Rome, opened in late1926. “To ensure that the new Breakers would be fireproofed and able to withstand storms that periodically hit the East Coast, the building was constructed using reinforced concrete and strengthened by 1,100 tons of steel,” Rose says.

Today, it’s perfection personified. “It’s the gold standard not just architecturally, but in service, style and food,” says restaurateur Bornia. “It’s incredibly well-run, and a beautifully maintained community of properties.” Among them are residential opportunities like apartments and condominiums, adjacent to the hotel.

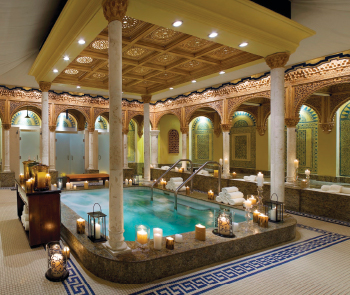

Boca Raton Resort & Club

The Boca Raton Resort and Club also dates to 1926, but was designed by Addison Mizner as the Cloister Inn. It’s in his signature style, one that defined early 20th-century architecture in The Palm Beaches by mingling Moorish, Gothic and Mediterranean influences. “Boca’s where Mizner settled in to really show off what he wanted to do,” Bornia says.

He aimed for nothing short of recreating the European Riviera. “It’s characterized by hidden gardens, barrel tile roofs, archways, ornate columns, finials, intricate mosaics, fountains, and beamed ceilings of ornate, pecky cypress,” says John Tolbert, president of the club and resort.

In 1930, under new owner Clarence Geist, Schultze & Weaver designed the resort’s current lobby. Mizner’s original, now referred to as the Addison Lobby, serves as the resort and club’s concierge desk. “This space has been preserved in its original form, including original furnishings, décor, and historical photography on display in partnership with the Boca Raton Historical Society,” Tolbert says.

A number of residential condominiums are available at this resort and club as well.

Norton Museum of Art

Change has been the mantra for decades at West Palm’s Norton Museum, a late Art Deco jewel designed in 1941 by Marion Sims Wyeth. He was an alumnus of Carrère and Hastings who’d set up his own Florida firm and designed Mar a Lago, now a Palm Beach retreat for the current resident of the White House.

The Norton’s prominently located on Dixie Highway, though renovations over the past few decades obscured that fact by moving its entrance to the south facade. “Driving by, you wouldn’t have sense of a world-class institution with a world-class collection,” says John Backman, project director at the Norton.

Enter Pritzker Prize-winning architects Foster + Partners. Over the past few years, they’ve restored the original east-facing entrance and placed signage prominently atop its cornice, while curators sited Oldenburg and van Bruggen’s “Typewriter Eraser” prominently next to its front door. The architects carefully accommodated an ancient Banyan tree that’s been growing out front since the museum was built, re-established Wyeth’s organizing east/west axis inside, and replaced a rear parking lot with a sculpture garden. “We were a 12-year-old Volkswagen, and then someone handed us a Lamborghini,” says a beaming Hope Alswang, the museum’s executive director.

While it’s true that the only constant in life is change, architecture in The Palm Beaches shows us how architecture can evolve gracefully over time – with a sense of style and dignity.