Ed Hollander is a landscape architect blessed with the wit of a standup comic. Ask him where he finds the inspiration for his larger-than-life designs, and he doesn’t miss a beat with his wise-guy, what-kind-of-question-is-that reply: “The New York Yankees?” he quips.

That’s why clients love working with him and architects can’t wait to collaborate with him. “He’s smart and funny, with common sense,” says Tom Kligerman, partner in Ike Kligerman Barkley in New York. “And he tells it like it is.”

“He’s got a great combination of enjoying what he does with a sense of humor,” says Marc Turkel, owner of Leroy Street Studio in New York. “He’s very canny and an expert in terms of knowledge and sensibilities.”

“He’s really down to earth and collaborative and speaks his mind,” says Blaze Makoid, founder of Blaze Makoid Architecture in Bridgehampton. “He’s very comfortable with where he is in life, and that makes working with him more relaxed, easy, and fun.”

Kligerman, Turkel, and Makoid are just three of the architects who’ve worked with Hollander in the Hamptons over the years. His first project there was back in 1991. “We did one with Robert Stern and interior designer Albert Hadley out in Quogue,” Hollander says. “Stern and Hadley were locked in mortal combat—Stern said to Hadley once: ‘Don’t you have any pillows and ashtrays to arrange inside?’ ”

But the project was featured in the New York Times Magazine, and Hollander’s career took off. He now estimates his firm has worked on close to 500 projects on Long Island. Along the way, he’s created some of the most site-sensitive, humanistic landscape designs out there.

“We tend to get pretty sophisticated clients and good architects,” Hollander says. “And it’s a magical interface between the land and the ocean.

Hollander was an undergraduate at Vassar in the late 1970s (“I got into botany because girls were interested when I’d bring in a plant,” he says); then he studied landscape architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, graduating in 1983. “That’s where the landscape kind of bloomed for me. I was the worst student at Vassar, but I was top of my class at Penn,” he says.

He learned from world-class instructors, including Ian McHarg, who founded the department and who Hollander calls “an apostle for the planner.” Also teaching were Laurie Olin and Ed Bye. Olin would later revitalize the grounds at the Washington Monument and develop landscapes for the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia.

After graduation, Hollander taught, first at Penn and later at City College in New York. He was offered the visionary Westway project in New York, an ambitious plan to plunge the West Side Highway underground and cover it with a huge urban park. Alas, it would have threatened the spawning grounds for striped bass. “That got it canned,” he says. “It was my last public agency project.”

He still thinks big, though, on a number of levels at once. “It took us a while to understand what our design process was, but there are three factors,” he says.

First is the site’s natural ecology, whether in the woods or along the ocean, and factors like sun and wind. Second is the architectural ecology. “We aren’t modernists or traditionalists,” Hollander says. “We’ll do traditional with [Robert] Stern and modernism with Steven Holl.” The third factor is people. Since every client is different, Hollander takes the human ecology into consideration.

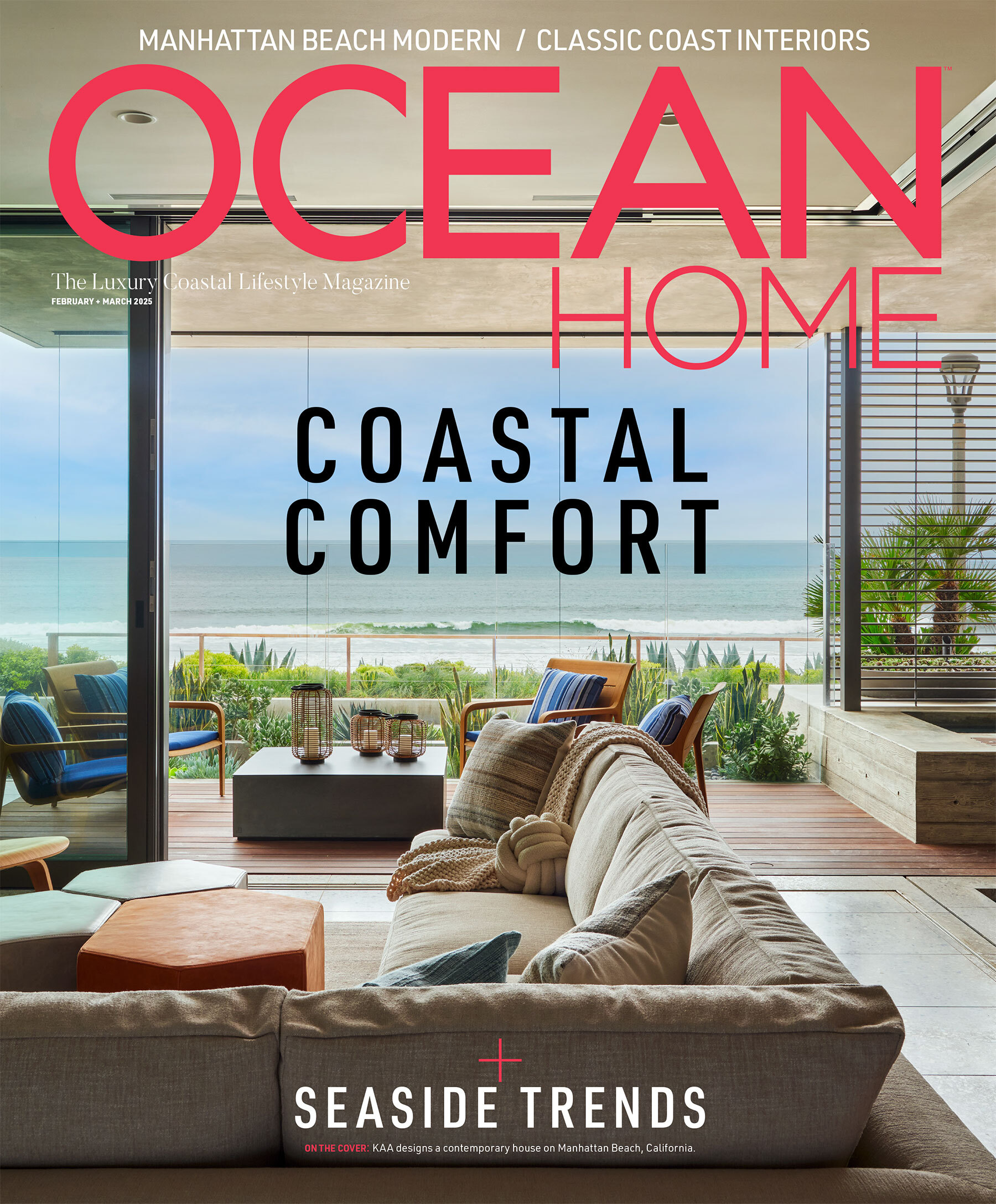

For the Lefcourt residence in the Hamptons pictured above, Hollander created a landscape design tailored around a modern house for a young family, with a series of living spaces set into the dunes. A shaded area with an outdoor kitchen hosts alfresco dining. Basically, the family lives in the natural environment.

“The wood decking is not fussy or high-maintenance, and all the plantings are organic, with no chemicals, no spraying,” he says. “It’s a kid-friendly and pet-friendly landscape on three quarters of an acre, so it’s not unmanageable.”

He paid particular attention to the children’s access to the pool area, designing it to be fully contained so young toddlers can’t get near. “Glass rails make it safe without obstructing views of the ocean,” he says. “There’s a small patch where the kids can throw the ball, with grasses that have adapted to growing along the ocean.”

Hollander’s not just interested in landscape design. One of his endeavors is the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art in New York. That’s where Peter Pennoyer, principal of Peter Pennoyer Architects, met him 20 years ago.

“It’s the most prominent organization in the country that promotes and teaches the classical tradition in architecture,” Pennoyer says. “It brings together architects, landscape architects, and artists—people who care about history. [Hollander’s] not a classicist, but he’s very interested in history.”

There’s also the annual Artists & Writers Softball Game in the Hamptons, where Makoid was introduced to Hollander eight years ago. “That’s his passion. It’s a charity event played every August, and he helps organize it. He plays with reckless abandon.”

As for his legacy, Hollander will leave behind an enormous body of sophisticated work plus three books about his designs. “He’s reshaped the American landscape and redefined the landscape for Eastern Long Island,” Kligerman says.

Best of all, he did it with a smile on his face.

For more information, visit hollanderdesign.com