Architect Paul Rudolph practiced in Sarasota for only a few years back in the 1940s and ‘50s, but the impact of his work is still being felt today.

Designers everywhere marvel at his Bauhaus-inspired Tropical Modernism–and at his Sarasota School of Design–that eventually spread like gospel across Florida.

His architecture was famously about place. “He was one of the people who introduced a very innovative type of modernism to Florida, one that investigated climate and terrain and materials,” says Timothy Rohan, author of “The Architecture of Paul Rudolph” (2014: Yale University Press).

A graduate of the architecture program at Alabama Polytechnic Institute—now Auburn University—Rudolph came to Sarasota in 1941 to join the office of Ralph Twitchell. Twitchell was a classically trained architect who, in the 1920s, had worked in Sarasota on John Ringling’s Venetian-style mansion, now a world-class museum.

But by the late 1930s, Twitchell was transitioning to the modern idiom, and Rudolph fit right in. His initial project was a house on Siesta Key for Twitchell and his fiancée. It would be the first of 24 that Rudolph designed for the firm in Sarasota and Bradenton. “Twitchell was good at getting the clients, and Rudolph was the creative side,” says Christopher Wilson, chair of the Sarasota Architectural Foundation.

But before the Twitchell residence was complete, Rudolph left to attend the Harvard Graduate School of Design, headed by German expat Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus. Among Rudolph’s classmates were I. M. Pei, Philip Johnson and Edward Larrabee Barnes, each destined for greatness in post-war America. Rudolph, his talent noted by Gropius, was selected for a coveted seat in the master’s class.

But World War II broke out in December 1941. Joining the Navy, Rudolph was assigned to duty in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. When the war was over in 1945, he fast-tracked his Harvard education, returning to Twitchell as an associate in 1948 and making partner in 1950.

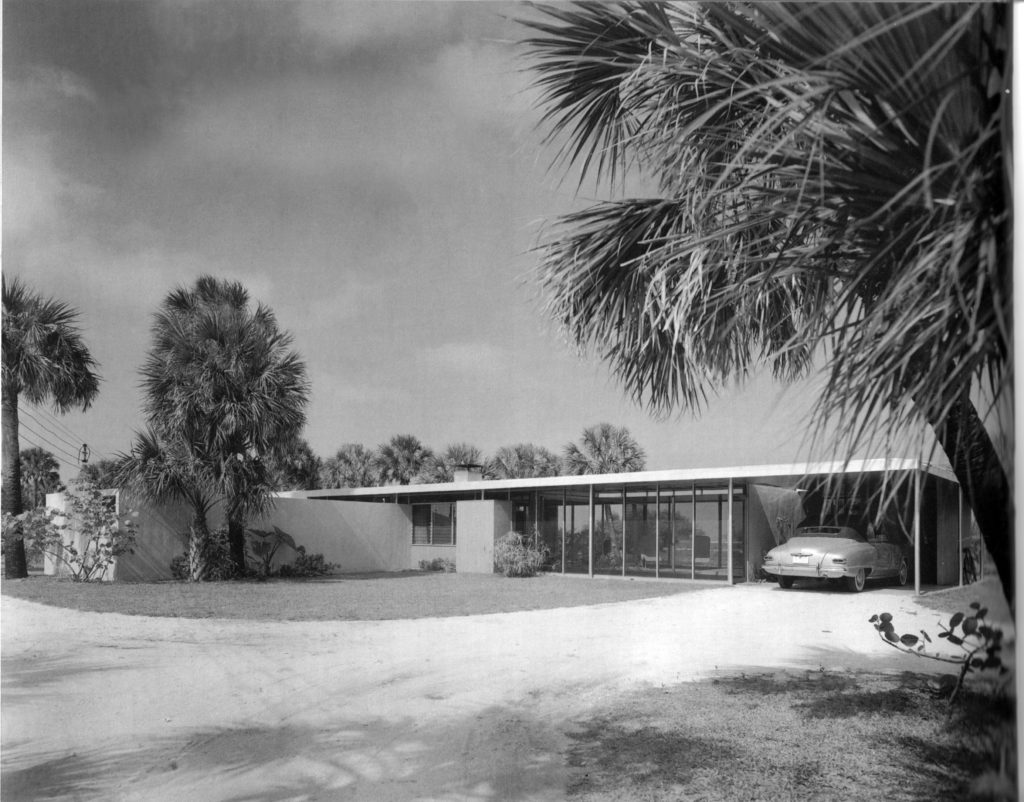

Many of their projects were second homes for Northerners and Midwesterners willing to explore a new kind of architecture in a tropical setting. “What he did most importantly was understand that these little second homes were going to be ‘Floridities,’ with screened-in porches,” says Miami-based architect Jacob Brillhart. “He recognized the environment – the sun, the rain and the mosquitoes – and he gave it another dimension.”

In the Navy, he’d become familiar with marine products like plywood, plastic and spray-on foam. And he put that knowledge to use in his designs for a new type of housing in Florida. Instead of pouring a concrete beam, he and Twitchell would take a pair of two-by-ten wooden beams and join them together.

“He understood structure – you can see the roof and the beams, with no decoration,” Brillhart says. “He said: ‘I’ll reveal it and make it thin and lightweight’ – and when you walk down the street, they stand out.”

His homes were sustainable before sustainability was hip—with passive cooling and heating that didn’t use much energy. “There are glass walls but they’re shaded with large overhangs that could also be an outdoor space,” Wilson says. “They extend the space and lighting by two because they’re protected from the top.”

Outside, louvers, shutters and clerestory window stimulated ventilation. Inside, Rudolph created spaces that flow into each other – before today’s much-desired open concept existed. “It’s modern architecture adapted for the Florida climate,” he says.

In 1948, Rudolph and Twitchell designed the Revere Quality House in Siesta Key, in partnership with Architectual Forum, Revere Copper and Brass Co. and builders Industries Lamolithic. There, one exterior glass wall faced the water, while the opposite wall was composed in glass, wood and crystal lattice. Opacity turned into transparency when blinds were opened. An enclosed central courtyard, illuminated by a rectangular roof opening, merged indoors and out – with a grass lawn and patio accessible from living and dining rooms.

Also on Siesta Key came the Cocoon House in 1951. Here, Rudolph experimented with a material used to store ships by the Navy: a spray-on foam called Cocoon. Sure, exterior louvers clad two sides of the 800 square-foot house, while the other two are glass. But it’s the roof that earned this home distinction. Steel straps that drooped, hammock-like, at the center were hung between two walls. Workers laid insulating panels across them and sprayed them with the shipping foam.

In 1952, developer Philip Hiss commissioned Rudolph for one of his first solo projects after he split with Twitchell. Known as the Umbrella House, it was to be an iconic symbol for Hiss’s Lido Shores neighborhood in Sarasota. Its “Umbrella” shade structure was composed of wooden uprights and tomato stake slats. Destroyed by a tropical storm in the 1960s, the home remained without its umbrella until restoration started in 2011. It’s now on the National Register of Historic Places.

By 1957, Rudolph had moved on to larger lots and more sought-after neighborhoods like the suburban Casey Key. There, he designed the Burkhardt House. Inside, public and private spaces are separated by a sunken, open-air living room that’s 22- by 40-feet. With 12-foot-tall ceilings, clerestory windows and full-height glass, the home was a lush and upscale step forward for the architect. Later owners added two more structures by New York architect Toshiko Mori.

Before he moved on to become chair of the Yale School of Architecture in 1958, Rudolph would design a total of 30 homes in Sarasota and Bradenton. Much of his later work – including Yale’s Art and Architecture Building and other structures in Asia – was in the brutalist style. That left him with mixed reviews, even after his death in 1997.

Still, he changed the face of Florida’s residential architecture in just 10 short years. “As Rudolph got those first houses built and the buzz started, the guys in his office broke out on their own. And some went over to Miami and brought that kind of thought to the East Coast,” Brillhart says. “His work had intellectual credibility and it was new. He could walk both sides of the fence.”

Where the Mediterranean Revival style of Addison Mizner once dominated Miami and Palm Beach, Tropical Modernism was suddenly de rigueur when graduates of Rudolph’s Sarasota School appeared on the stage.