Sporting a whimsically shaped silhouette, this petite Fishers Island cottage shaped like an observation tower instantly piques the interest of anyone curious about house design. But long before the first foundation stone was laid, or cedar shingle nailed into place, the architect-owners frequented the undeveloped parcel teeming with invasive plants just to make sure they understood the canvas upon which their house would be built.

“Just as important to us as the architecture of the house was the setting, the landscape architecture, and the site itself,” says Stewart Skolnick, cofounder of Haver & Skolnick. He and his partner, in business and life, Charles Haver, run their architecture firm out of a restored 18th-century carriage house in Litchfield County, Connecticut. “We wanted to make sure we understood the potential of the land so that we could site the house properly,” concurs Haver.

Much of the potential the two were eager to grasp consisted of views of the Atlantic Ocean and of some of the island’s 350 acres of protected conservation land. “On a clear day, you can see Montauk Point,” says Skolnick, adding that you can also glimpse several ponds—one for oyster cultivation—that surround the property. “There are reflections of water all around the house.” On this sparsely populated island, Pointer Perch, named after their German shorthaired pointer, Keeper, overlooks only nature as far as the eye can see. Even the outdoor shower offers a glimpse of the ocean.

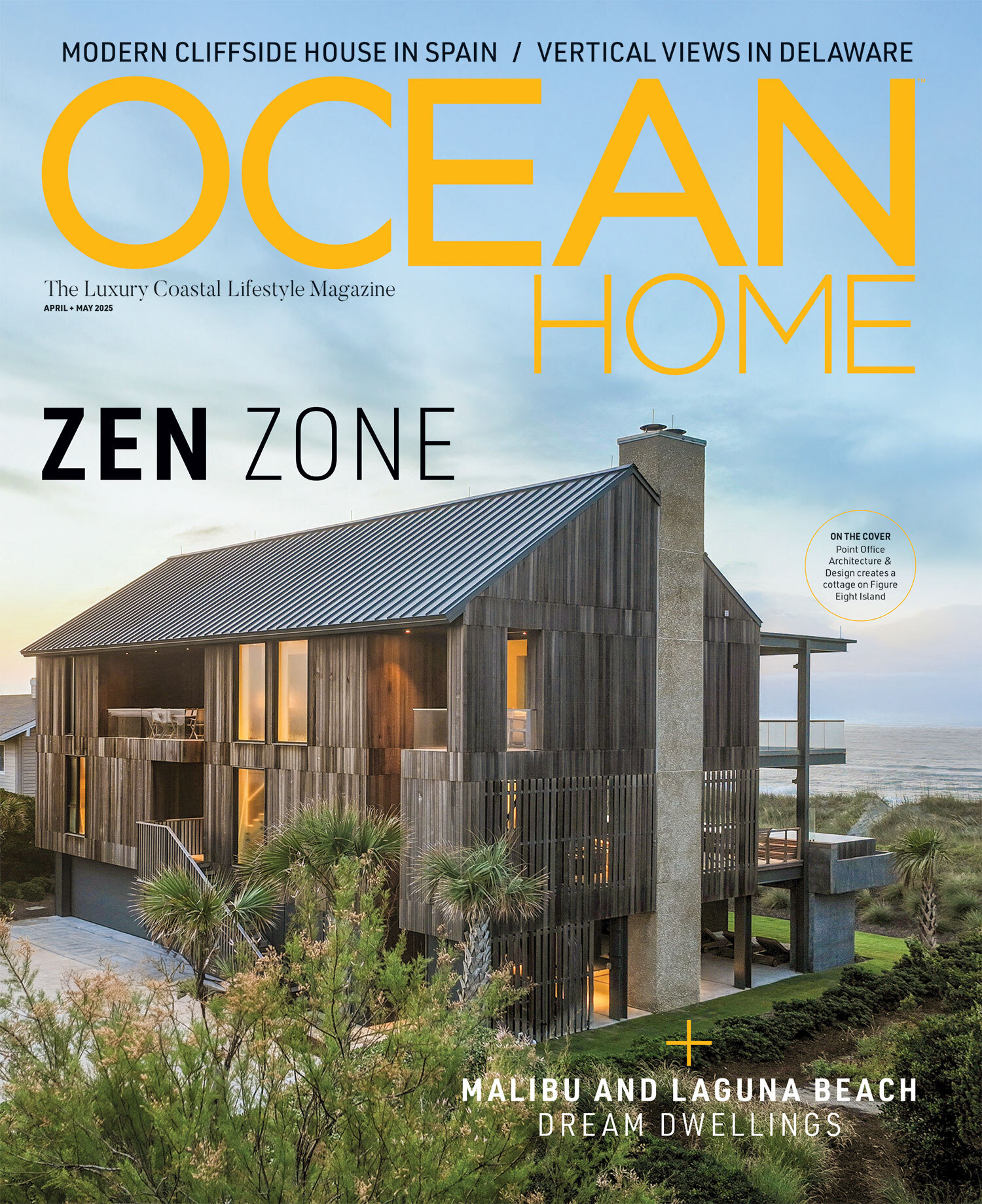

The higher up you go on this unique parcel of land, the better and more expansive the views. “That’s really what the driving factor was in the design of the house,” says Haver of the structure’s accentuated verticality. To capture the views on all sides, the building has the living spaces on the second floor, with the primary bedroom and mudroom area below. The small kitchen sits in a dormer created by the back side of the hip roof. “It’s a very dynamic form, but its vocabulary is rooted in the Shingle Style, in which the bulk of the island’s houses were built,” explains Skolnick.

Most of Fisher Island’s approximately 600 houses were built in the 1920s, the same era Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., was hired to plan a private 1,800-acre residential development on the island. The stock market crash of 1929 dramatically slowed development.

When Haver and Skolnick were mulling the design of the building, they took their time, going through nearly a hundred different schemes over the course of a decade. “In the end, we decided we should just design for what we need,” says Haver. “It’s a weekend and vacation retreat, so the simpler it can be in terms of maintenance, the better.” The Alaskan yellow cedar shingles, bronze railings, and charcoal gray aluminum-clad windows they chose for the exterior will weather over time. Exterior paint, needing occasional touch-ups, is limited to the front door and the walkout basement’s mudroom door.

Having spent so much time walking the property before building on it, the two men say it was a quick decision to build not only a small house—it has a single bedroom and one full bath—but also one that blended effortlessly with the existing landscape. It was important for them to keep the house very rustic and low key.

Inside the 1,200-square-foot home, walls and ceilings painted crisp white pair with rift- and quarter-sawn oak flooring and hand-hewn beams. “Nickel-gap paneling gives it scale and recalls what an older porch might look like,” observes Haver.

For the two architects, it was a challenging exercise—one they often employ with their clients—to ascertain the minimum they needed to be comfortable. “When we started out, we had a guest room on the lower level,” explains Haver. Acknowledging that they don’t have company often, they opted instead to use the space for sorely needed storage. An outdoor shower was a must.

The combined living and dining space on the second floor “pretty much does everything for us,” says Haver. The only other room on that level is a small kitchen. “Because we like living very simply, we deliberately didn’t want any hanging cabinets,” says Skolnick, explaining why they opted for open shelving. “We wanted to be able to easily reach for a glass or a plate.” The pyramidal ceiling in the kitchen is a miniature version of the one in the living room, each a perfectly square space.

“We like living with antiques,” says Skolnick. “In Connecticut, we have a lot of Americana pieces; here we deliberately chose to go with European—French, Italian, and Spanish.” The two men also have a penchant for contrasting antique furnishings with modern abstract art, which hangs throughout the home. “So much of what we do as architects has to be very precise,” says Skolnick. “When it came to art, we wanted something that would be anything but that.”

Similarly, the paths cut through the meadow, the driveway, and the planting beds are all undulating, curving forms, because, says Skolnick, “In nature, you don’t find right angles.”

Stacked from the road down to the ocean, the two lots Haver and Skolnick purchased total 3.1 acres. They donated the lower lot to the Henry L. Ferguson Museum Land Trust, which owned all the land on the south and east side of them already, and retained the right to maintain the view and the meadow. “We knew that we would never want that lot to be developed, and by giving it to the land trust, we’ll never be tempted to do anything there, nor will anyone else in the future,” says Haver.

“Overall, we’re very pleased with the house,” says Skolnick. “It feels like pulling on an old sweater and it feels really good. It suits us.”

For more information, visit haverskolnickarchitects.com